Additional Content

*NYU Login Required NYU Urban Democracy Lab Blog

Baseball as Urban Practice:

The Relocation of the Oakland A’s

I had never considered myself a die-hard sports fan. Sure, I’ve always appreciated a good pastime — the crowd energy, the occasional dramatic comeback — but I’ve never felt tethered to a team like some people do.

In part, I’d say that has to do with my geographic dislocation from local teams. I was born in San Francisco but grew up in the suburbs of the East Bay, close enough to both cities to feel adjacent but not embedded in their culture. I didn’t think there was a big difference between supporting Oakland’s major league sports teams or San Francisco’s — but that’s the kind of thing you only believe when place hasn’t asked much of you. I stuck with generalized support and indifference, while for people who grew up in the heart of either city, the rivalry ran much deeper.

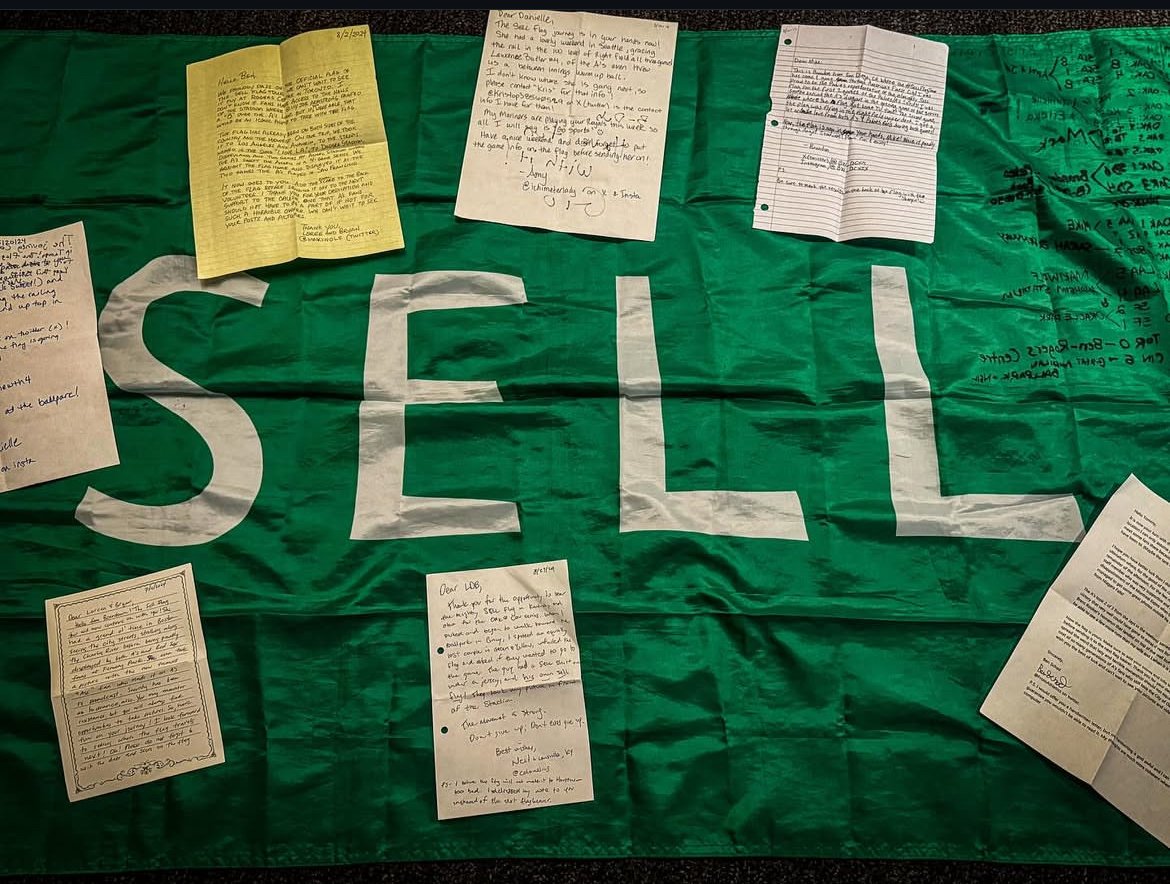

Mosaic of the Oakland Coliseum made from fan photos in "SELL" gear—protest art by Last Dive Bar, spotted in a San Francisco gallery. 2024.(Coursey of the Last Dive Bar and SFMOMA)Introduction: More Than a Sports Story

As long as Damian could remember, they had attended Athletics games at the Oakland Coliseum just down the road. “It was like a home away from home,” they told me one summer day during an interview in the BART parking lot adjacent to the Coliseum. Damian spent countless hours at the Coliseum, not just as a fan in the stands but as a kid growing up in its orbit. Even the BART parking lot held memories. Damian recalled how, back when the Coliseum drew big crowds, the overflow lot was informally run by a local unhoused man who, for a few bucks, would keep an eye on your car and make sure it didn’t get ‘bipped’ — broken into. For many kids growing up around the Coliseum, it was more than just a ballpark — it was a rare space of safety and joy. Youth camps, community nights, and Little League games created a sense of belonging that extended beyond the field. Damian remembered those days vividly, surrounded by other neighborhood kids and families who made the stadium feel like an extension of home. “Sometimes my parents would sneak Hennessy into the Coliseum by wrapping it in my swaddle,” they said, laughing. It was a place where families could gather, relax, and just be, without pretense, without worry.

Oakland’s ‘Thereness’

Stein’s framing becomes particularly potent when considering the recent decision to relocate the Oakland Athletics—a team that, despite winning the 1989 World Series against the San Francisco Giants, has spent decades in their shadow. The feeling "there is no there there" resonates not just in the abstract sense of urban identity, but also in the physical, communal, and symbolic erosion represented by the loss of the Athletics and the eventual abandonment of the Oakland Coliseum—a space once filled with noise, pride, and possibility. In this context, the Stein quote does more than capture a historical disorientation; it becomes both a rationale and a self-fulfilling prophecy. The belief that there is no "there" in Oakland helps justify the decision to strip it of yet another institution, even as that very act deepens the sense of erasure and dislocation that was originally lamented.

That same feeling persists for Damian, who returned to East Oakland only to find their childhood landmarks altered and erased. The corner stores are closed, the neighbors have changed, and even the Oakland Coliseum—the once-vibrant home of the A’s—feels hollowed out. Like Stein, Damian is confronted with the eerie sensation that the place they remember no longer quite exists. Her reaction, like Damian’s, reflects a genuine sense of dislocation—an acknowledgment of how much Oakland had changed, and how the familiar landscape of their memories had been overwritten by new development. At the same time, that original observation of a lack of ‘thereness’ has been severed from its context and repurposed as justification for the city’s further displacement and reinvention — as if the absence she once named were permanent and unfixable.

And a (re)Awakening

Children Prepare Bags of Food for Distribution at the Oakland Collesium at the Black Panther Community Survival Conference, Oakland, March 1972.(Courtesy of Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)Now, in the wake of the Athletics’ departure, residents like Damian are asking sharper questions about what civic investment should look like. While Damian still wishes the team had stayed under different ownership, they see value in the city’s refusal to fund a new stadium with public money. In their eyes, this was not just a rejection of billionaire demands—it was a moment of political clarity. A refusal to repeat a decades-long cycle in which corporate interests are privileged over community needs.

Oakland Athletics' Rickey Henderson, right, and Dave Henderson head to the outfield on April 5, 1992.Life in East Oakland poses harsh and often unforgiving challenges for young Black people and families. The socio-economic landscape is shaped by disinvestment, surveillance, and limited resources— conditions that funnel too many into the school-to-prison pipeline.

Damian’s family lived this reality. Both of their parents witnessed and experienced suffering from a young age. Damian’s father lost his best friend to gun violence in high school, forever altering his life. Damian’s father soon became a teen parent and was incarcerated.

Despite this, Damian’s parents — especially their mother — always did their best to ensure that Damian would succeed. From church to private school, to baseball games, Damian’s mom always made sure they were in safe environments. “The Coliseum was a big part of that,” Damian explained to me. It wasn’t just the riveting games or baseball idols like Rickey Henderson, but also the environment through and outside of the Coliseum space that allowed them to exist in safety and community with others. From tailgates in the parking lot to fireworks nights under the open sky, the Coliseum provided space for Damian and many other children to foster a more positive relationship with Oakland.

But that feeling has eroded. Today, fewer and fewer Black kids grow up playing baseball. In 2024, only 6% of Major League players were Black—a number that used to be three times as high in the early ‘90s. The reasons are layered: disinvestment in public parks, the high cost of youth travel leagues, the disappearance of baseball programs in underfunded schools. But it also feels like the sport has drifted—become something else entirely. Something more exclusive, more corporate. Less about place, more about profit.

In Oakland, where a team is gone and a stadium sits in limbo, these shifts feel especially sharp. The promise that baseball once held—a shared public good, a local identity—is harder to see now. The dream of civic pride has collided with the reality of late capitalism: private owners, public funding, and communities asked to sacrifice without much return. Maybe the question now isn’t how to bring baseball back—but what kind of city we want, and whether sports like this can still belong to the people who live there.

The Sell Movement

By the summer of 2024, the writing was on the wall: the Oakland A’s were leaving despite promising proposals and the community’s commitment to protest. But instead of going quietly, fans and community members launched a coordinated, defiant campaign to resist not just the relocation, but the corporate decisions that made it feel inevitable. The Sell Movement peaked during this Summer of Boycott.

This was the moment my research truly began. The team’s exit was only the surface. What I found beneath it was a city actively reimagining its identity through protest, memory, and organizing. I began meeting with community members—people who had grown up going to games, people fighting for housing justice, port workers, artists, longtime East Oakland residents. Their reflections, political commitments, and lived experiences form the core of the next section: a series of interviews that attempt to archive what this summer felt like, and what it meant to resist the erasure of Oakland’s civic soul.

The Signs of Belonging

Among the most enduring visuals in Oakland’s recent history is the “Rooted in Oakland” sign that once overlooked the freeway from the Coliseum wall. First unveiled as part of the A’s branding strategy after John Fisher’s acquisition of the team in 2017, the phrase quickly took on deeper meaning for the community. Paired with the stylized Oak tree—Oakland’s city logo since the 1970s—the mural suggested not just team loyalty, but a rootedness in place, memory, and collective identity. It became a kind of shorthand for what was at stake.

By early 2024, as relocation became inevitable, the mural was removed. Its disappearance was more than cosmetic—it marked a symbolic erasure, a preemptive rewriting of the city’s visual and emotional landscape. But instead of fading quietly, the imagery was absorbed into the visual grammar of the movement that rose up in response.

Signage in this context functioned not just as protest but as cultural memory—portable and visible expressions of who the team really belonged to. As scholar Christina Zanfagna writes, cities like Oakland are full of “symbolic reclamations,” where signs, slogans, and public art serve as both documentation and defiance.

The Oakland Athletics' relocation has precipitated a significant economic upheaval, resulting in the loss of nearly 600 jobs tied to the Coliseum, including concession workers, ushers, ticket takers, and front-office staff . Many of these employees have dedicated decades to the team, and now face unemployment without severance pay or continued health benefits. While the A's have established a $1 million Vendor Assistance Fund, the support it offers is limited and does not adequately address the needs of the displaced workforce.

Moreover, this formal acknowledgment overlooks the informal economy that thrived around the Coliseum. Independent vendors, local entrepreneurs, and community members who relied on game-day commerce in the parking lots and surrounding areas are left without recourse or recognition. Their livelihoods, woven into the fabric of East Oakland's economy, have been disrupted without compensation or support. This oversight underscores a broader pattern of marginalization, where the economic contributions of informal workers are disregarded in the face of corporate decisions.

The relocation thus not only displaces a sports team but also dismantles a complex ecosystem of formal and informal labor that sustained the community. It highlights the need for more inclusive economic considerations that value all facets of the workforce, especially those operating beyond traditional employment structures.

Community Archive

My summer was spent attending boycott events, Athletics games, and arranging interviews. I met with various community members of diverse backgrounds — longtime fans, merchants, and notable figures in the Sell movement. The following excerpts document the honest reactions, insights, and complaints of the community the team left behind.

Jorge Leon is the founder of the Oakland Athletics fan group the Oakland 68s and a recently appointed board member of the Oakland Ballers, a minor league team formed largely in response to the A’s relocation. I met Jorge before a game as he gathered with other reverse boycotters wearing SELL gear. When asked how the Athletics contribute to Oakland culture, Jorge flipped the question—emphasizing instead the importance of Oakland’s culture to the identity of the team.

At 13 years old, everything changed when Damian’s family made the difficult decision to leave their home. The rising cost of living had made it harder to stay, and their house — perched along the San Andreas Fault — had become a growing liability. Safety and affordability ultimately took priority over memory and place. Since then, Damian has lived all over the Bay Area — and was in Antioch with their mother and grandfather when I first met them in 2021. Soon after I started college, Damian’s mother and grandfather moved to Texas — and Damian ultimately ended up back in East Oakland, living with their father, just down the road from where they grew up. Despite a seemingly full-circle moment, that initial loss at 13 continues to impact their relationship with the ever-changing landscape of Oakland. “It’s left a big effect on me till this day,” they told me, “where it's hard to find a sense of home anywhere — even here.” Returning to an unfamiliar Oakland — rapidly gentrified neighborhoods, profound loss of retail presence, and a shifting racial demographic — Damian finds themselves reckoning with a city that looks like home but no longer feels like it.

Initially founded during the Gold Rush, the East Bay portside city of Oakland has since become a diverse mecca and trading hub, home to around 430,000 mostly working-class Americans. Yet the city’s identity has long been shaped by rupture through waves of development and displacement. The 1890s marked one of the first significant turning points in the feel of Oakland, as farmland gave way to neatly plotted neighborhoods. When Stein returned to the city during this period, she found her childhood home gone and declared in Everybody’s Autobiography that “there is no there there.” Her words reflected a genuine sense of loss—the kind that arises when the landscape of memory is overwritten by a new and unfamiliar city.

The dislocation Damian has felt since returning to East Oakland echoes a much older kind of estrangement—one famously captured by Gertrude Stein in 1890.

Author Mitchel Schwarzer of Hella Town: Oakland’s History of Development and Disruption began his book with a critique of this very quote, emphasizing how, “Her words have since underpinned a false impression that Oakland is lacking in something, in someplace” (Schwarzer 1). This perceived absence of identity, of rootedness, has haunted Oakland’s urban development throughout the 20th century and into the present day. It’s the sense of a place often defined by what it is not, especially when viewed in contrast to its more glamorous neighbor across the Bay. Oakland is “the town,” while San Francisco is “the city.”

The story of the Oakland Coliseum begins not with a game, but with a freeway. Long before the Raiders or Athletics arrived, city planners imagined the stadium as a kind of urban punctuation mark — a civic monument to mark Oakland’s modernity. In 1950, Oakland city planning engineer John Marr floated the idea of building a municipal baseball and football stadium near the Eastshore Freeway, just off Hegenberger Road on the way to the airport. What followed was over a decade of maneuvering to land a professional team and prove Oakland’s worth — to challenge the persistent notion that there was “no there there.” The Coliseum, in this light, was more than a sports venue. It was an answer. A declaration that Oakland was a city worth rooting for.

The 1950s were consumed by attempts to lure a football franchise to move to Oakland. As Schwarzer writes, “it became known that Oakland had a shot to land the last of eight franchises in the new American Football League… Barron Hilton, the influential owner of the Los Angeles Chargers, loved the idea of a second AFL team in California and the north-south rivalry it would engender. Oakland became the logical choice” (Schwarzer 147). Once the Raiders were secured, a nonprofit called “Coliseum Inc.” was formed under Robert Nahas — the same businessman responsible for the Oakland Museum project. Coliseum Inc. tapped Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM) to design the venue. Though SOM had never built a stadium before, their San Francisco presence and reputation for scale made them a natural pick. By 1963, the project was approved for a “48,400-seat outdoor stadium and 13,500-seat indoor arena,” imagined as a local economic engine and flexible site for community events like high school sports and horse shows (Schwarzer).

Constructing the Coliseum: A Misguided Vision

Construction began in May 1964 under contractor Gus F. Atkinson, and the Coliseum officially opened in September 1966 when the Raiders played the Kansas City Chiefs. "Oakland lost. But a little over a year later, Oakland got back at Kansas City — through baseball,” Schwarzer writes (148). The Kansas City Athletics were relocated to Oakland in 1967 by owner Charles Finley, enticed by the brand-new stadium. In what Schwarzer calls a “fantastic coup,” the Coliseum attracted teams in all four major league sports between 1967 and 1977 — including the Seals (hockey) and Warriors (basketball).

But this grand civic project carried costs that extended far beyond its concrete walls. While it was envisioned as a catalyst for East Oakland’s growth, the Coliseum quickly became a case study in stadium failure: underestimated construction costs, overestimated revenues, and a lasting financial burden on the public. “Between 1966 and 1991, there were no profitable years. More often than not, then, the complex required annual taxpayer subsidy,” Schwarzer writes (151). This model — flashy promises, little return — disproportionately impacted the very neighborhoods that shared its fence line. It’s here, in the shadow of the Coliseum, that the story turns to the people of East Oakland — particularly Black Oaklanders — who paid the steepest price for the city’s sports ambitions.

Oakland-Alameda Coliseum 1966.(Courtesy Hearst Newspapers 1966)The Decision to Leave

The decision to relocate the Oakland Athletics to Las Vegas resulted from a complex set of political and economic circumstances. In part, it was fueled by escalating tensions over the coliseum’s lease held between the team’s ownership and the city government, failed negotiations to build a new stadium dependent on Oakland taxpayer dollars — but ultimately it was the lure of Las Vegas’ tax incentives and promise of a larger revenue stream that sealed the deal. Yet, at the heart of this decision was a deeper story — one about the forces of gentrification, racial capitalism, and the prioritization of corporate interests over the desires of Oakland’s residents. For decades, the city’s leadership had struggled to balance the demands of developers and corporate entities with the needs of its working-class residents, the majority consisting of communities of color. Compounded by business losses during the COVID-19 pandemic and pending federal corruption charges against the city government, the prospect of reaching a feasible agreement with Athletics owner John Fisher became increasingly unrealistic as the deadline approached. The move was unanimously approved by MLB ownership at the Owner’s Meeting on November 16, 2023.

In response, The Last Dive Bar shifted from collaboration to activism. They spearheaded the "Sell the Team" movement, organizing protests and boycotts that resonated beyond Oakland. One notable event was the "reverse boycott," where fans filled the Coliseum to capacity, not to support ownership, but to demand change. Their efforts symbolized a broader resistance against the commodification of sports and the erosion of community-centered values. Thus a movement was born.

Bryant, reflecting on this transformation, emphasized that the movement was about more than baseball. It was a stand against the corporatization of a cherished civic institution and a fight to preserve the communal spirit that the A's once embodied. The Last Dive Bar's journey from partnership to protest encapsulates the tensions between local identity and corporate interests, highlighting the profound impact such shifts have on communities

“Though a radically different kind of setting for a home, the third place is remarkably similar to a good home in the psychological comfort and support it extends... They are the heart of a community’s social vitality, the grassroots of democracy, but sadly, they constitute a diminishing aspect of the American social landscape.”

Table of Contents

It wasn’t until I met my partner, Damian Irvin — a Black Oaklander and lifelong Oakland Athletics baseball fan — that I began to understand how a sports team could come to represent something bigger than the game itself. Damian spent their early years in a multigenerational home on Blandon Road in East Oakland, a short drive from the Oakland Coliseum. This home belonged to their grandparents, who had moved from San Angelo, Texas, to Oakland shortly after they were married in the 1960s, during the last wave of the Second Great Migration. Like many Black Americans during that era, they were drawn to Oakland by the economic opportunities created by its booming trade, manufacturing, and defense industries, as well as the chance to live in a place that offered more social and political freedom than the Jim Crow South. The Kennedy’s made their home there, raising both Damian’s mother and eventually Damian under the same roof. Surrounded by family and longtime neighbors, Damian grew up with a deep sense of rootedness — a connection to a place that shaped both their love for Oakland and their loyalty to the A’s.

Near Stein's Home 1899.(Courtesy Oakland Public Library, Oakland History Room)Within the Context of Baseball

Baseball’s Last Dive Bar

The Last Dive Bar began as a grassroots fan collective, rooted in love for the team and the unique culture of the Oakland Coliseum. Bryan Johansen was inspired to start the Last Dive Bar after the Athletics posted a meme of his bewildered reaction—now famously known as the "Bryan WTF" GIF—on Twitter, sparking a wave of fan-driven camaraderie and irreverent defiance.Their name came from a tongue-in-cheek line in a 2021 SF Chronicle article that referred to the Coliseum as “the last dive bar in baseball”—a nod to its no-frills charm, crumbling concrete, and fiercely loyal fans. The phrase stuck. Embracing the identity, the group began producing merch that celebrated the grit and history of the A’s and their home stadium, often donating proceeds to local charities and community causes. At the time, their relationship with the team was collaborative. The franchise allowed them to set up merch tables at games, and there was a mutual respect rooted in shared Bay Area pride. The Last Dive Bar helped sustain the mythology of the A’s as lovable underdogs: scrappy, affordable, and defiantly anti-corporate in a region increasingly shaped by tech money and gentrification. They weren’t just fans—they were stewards of something sacred. That made the betrayal sting even more when ownership began undermining the city and its people in pursuit of a glossier, more profitable future elsewhere.

Bryan Johansen, co-founder of the Last Dive Bar, helped transform a fan-driven merchandise project into a powerful advocacy platform for Oakland A’s supporters. At a Battle of the Bay boycott event at a local brewery, he recounted the grassroots origins of the Last Dive Bar movement, expressing both heartbreak and determination as he looked ahead to what comes after the A’s leave town. Despite the team's departure, Johansen remains committed to preserving Oakland's baseball culture through community events and continued activism.

Before the relocation was finalized and the fanbase fully galvanized, The Last Dive Bar emerged as a quiet but determined nucleus of resistance. In the early days of the Sell movement—long before the summer of 2024, when relocation felt inevitable—there was still a sliver of hope that the team might be sold to a local owner who would keep the Athletics in Oakland. Negotiations between the city and the front office were tense but not yet broken. During this liminal period, The Last Dive Bar shifted its energy from quirky fan culture to political advocacy. What began as playful slogans and limited-edition shirts gradually turned into sharper, more pointed messaging. The group helped articulate a collective desire to see the team stay rooted in the community, channeling growing public frustration into a clear demand: John Fisher must sell. Their early merchandise doubled as organizing tools, sparking conversations in bleachers, bars, and online forums. These initial stirrings laid the groundwork for what would become a mass protest movement—one that, even then, was beginning to ask deeper questions about civic loyalty, ownership, and what it means to lose more than just a sports team.

Summer of Boycott

It was also a summer of deep political crosscurrents. While fans were boycotting the Coliseum, pro-Palestinian organizers were shutting down terminals at the Port of Oakland. These actions, led by Bay Area dockworkers, students, and grassroots coalitions, marked some of the most visible local responses to the war on Gaza and the run-up to the 2024 election. The symbolism wasn’t lost on anyone—Oakland, long a hub of anti-imperialist labor organizing, was once again asserting itself as a place where local and global struggles converge. In that same spirit, The Last Dive Bar began fundraising for other community causes, partnering with mutual aid groups and redirecting fan energy toward forms of solidarity that extended beyond the stadium walls.

Meanwhile, grassroots sports organizing in Oakland is gaining momentum, offering a more community-rooted vision of athletic culture. The Oakland Ballers, an independent baseball team founded in 2024, have garnered support from local figures like Billie Joe Armstrong and Too Short, aiming to revive baseball enthusiasm in the community. Similarly, the Oakland Roots SC and Oakland Soul SC soccer teams are fostering local pride and engagement, with the latter planning to join the first-division USL Super League pending the construction of a new stadium.

For decades, the Oakland Coliseum has stood at the intersection of civic promise and civic betrayal. Just miles from where the Black Panther Party was founded in 1966, the stadium has long symbolized conflicting visions for Oakland’s future—visions shaped by race, class, and political power. The Panthers imagined a city in which public resources were used to serve the people, not siphoned off to prop up elite interests. Bobby Seale’s 1973 mayoral campaign made this vision explicit, openly criticizing the Coliseum’s construction as a misuse of taxpayer dollars. As historian Mitchell Schwarzer writes, “The Black Panthers framed Oakland’s patronage of the Raiders as part of the political and economic dynamic that contributed to the oppression of urban Black neighborhoods” (151).

BPP Members Demonstrating Outside the Alameda Court HouseDuring Huey Newton Trial.(Courtesy of Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)To many in East Oakland, the Coliseum wasn’t just a stadium—it was a fortress. Its promise of economic uplift never materialized for the neighborhoods around it. Despite city efforts to attract development—hotels, restaurants, retail—these ambitions stalled. What flourished instead were storage centers and warehouses, logistics infrastructure that bypassed the community in favor of industry. “On what had seemed to be prime retail land,” Schwarzer notes, “warehouses, distribution centers, and storage facilities have long predominated” (153).

Adjacent to the Coliseum, Lockwood Gardens public housing stood as a stark counterpoint: densely populated, historically under-resourced, and frequently used as evidence of failure rather than a call for investment. These were not unfortunate outcomes—they were baked into Oakland’s approach to development, which treated East Oakland less as a neighborhood and more as a speculative zone. While a major redevelopment plan was eventually passed for the Gardens, it did little to address the deeper neglect or shift the structural logic that had long marginalized the area—another instance where “improvement” masked continuity.

In turning down John Fisher’s proposal, Oakland refused to validate a familiar script of public sacrifice for private profit. That decision, Damian believes, could mark a shift: a chance for the city to reassess how it uses its resources, who its urban policies are designed to serve, and what kind of future it owes to those who have long called it home.

The loss of the A’s, painful as it is, has also created space. It has prompted a reckoning—not just with what Oakland has lost, but with how it wants to build forward.

Baseball has always carried a kind of civic and racial weight. For a long time, it offered cities like Oakland more than just a team—it was a symbol of belonging, of working-class pride, of public life. The stadium was a place where people gathered, where local politics and neighborhood identity met the spectacle of sport. And for Black Americans especially, baseball once represented a rare and visible crack in segregation’s wall. Negro League teams were not only sources of entertainment but also pillars of economic and social cohesion, supporting Black-owned businesses and providing communal pride during segregation. Jackie Robinson’s debut, in particular, wasn’t just a baseball moment—it was a national one, and it meant something deep to communities who saw in him the possibility of something different. In Oakland, that lineage lived on through players like Rickey and Dave Henderson, who felt at home in the Black city and became local heroes—idols to kids like Damian who saw in their success a reflection of their own streets and dreams.

It was during the last summer the A’s played in Oakland that I witnessed firsthand the intensity of this movement, as the city braced for its final season with the team. The summer of boycott was palpable, with fans and activists organizing protests at games and boycott events. I connected with The Last Dive Bar, the organization at the forefront of the call to sell the team. At a boycott event, I met Bryan Johansen, one of the cofounders. Meeting Bryan was a turning point for me, as it solidified my understanding of the movement’s broader implications — this wasn’t only about keeping the A’s in Oakland, but about preserving the city’s soul.

The Last Dive Bar emerged as a central node in this reclamation. Originally a fan-led merchandise brand celebrating Coliseum in-jokes and A’s culture, the group began producing gear that explicitly called out ownership and supported the boycott. Their products—hats with slogans like “SELL,” shirts reading “Fisher Out”—echoed the language of protest while maintaining the insider tone of a subculture. In this way, The Last Dive Bar helped transform sports fandom into an act of collective resistance. What began as merch became message.

The shift from “Rooted in Oakland” to “SELL” captures the semiotic arc of the movement: from place-based pride to oppositional protest. Both phrases, grounded in signage, became tools through which fans not only expressed grief and frustration but reasserted their presence. These symbols allowed fans to remain visible, legible, and rooted, even as the physical team was being uprooted.

Displaced Labor

Casey Pratt, once a trusted ABC7 sports anchor and key source for A’s fans following the relocation saga, spoke to me just after shifting into a new role as Chief of Communications for the Oakland Mayor’s Office. Offering insight from both journalism and city government, he pushed back against misleading narratives about Oakland and detailed the city’s failed negotiations with the team. Now, just seven months later, Casey has pivoted again—this time to become Vice President of Communications & Fan Entertainment for the Oakland Ballers.

What Now?

The Oakland Athletics played their final game at the Coliseum in 2024 and are now, unceremoniously, biding their time in Sacramento—sputtering through a lackluster season on a minor league astroturf field in one of the sunniest cities in California. The temporary relocation feels both surreal and insulting to longtime fans. Damian, once a devoted supporter, has grown openly resentful since the move, wishing nothing but suffering and embarrassment on the team as they flounder through this transient moment.

But while the A’s drift in limbo, the city of Oakland is reverberating with response and resolve. The Oakland Coliseum is undergoing a major transformation, as the city has sold its share to the African American Sports and Entertainment Group (AASEG), which plans to redevelop the site into a multi-use complex that includes housing, sports facilities, and entertainment venues. AASEG's vision includes a $5 billion megaproject featuring sports, entertainment, a hotel, and new housing, with a focus on revitalizing the community and minimizing displacement or gentrification.

As the A’s prepare for a controversial move to Las Vegas, Oakland is already writing a different kind of future—one rooted in local power, memory, and possibility.

At its core, urban practice refers to the ways people engage with, shape, and respond to the social, spatial, and political dynamics of the city. It encompasses both formal interventions—like planning or design—and everyday acts of place-making, protest, memory, and belonging. Through this lens, baseball in Oakland is not just a sport but an urban practice: a deeply embedded ritual that reflects and refracts the city’s racial, economic, and cultural history. The game, as played and watched at the Coliseum, has served as a site of communal gathering, neighborhood identity, and political struggle.

By approaching the A’s departure ethnographically, I came to understand how people resist erasure not just through slogans or headlines, but through memory, mourning, and improvisation. I witnessed fans turn grief into ritual, from “reverse boycotts” to jars of Coliseum dirt sold like relics. I saw how spatial belonging was remapped in chants, shirts, murals, and in the refusal to forget. Baseball, here, became a language for expressing urban displacement—and for contesting it.

This project has shown me that urban practice is not just about how cities are built or organized, but how they’re felt, lost, and reclaimed. In Oakland, the fight for a baseball team became the fight for something bigger: the right to stay, to remember, and to be heard.

Conclusion: Baseball as Urban Practice

Thanks to Sam Dinger, Keith Miller, Jacob Remes, and the Urban Democracy Lab for supporting this research. Deep love and gratitude to my partner, Damian Irvin, and to the City of Oakland—thank you, always and forever.